Chapter 31: Configuration Files & Types of Shell

Index

- Introduction

- Available configuration files

- Types of Shell

- A Note on Non-Interactive Non-Login Shells

- Summary

- References

Introduction

Bash includes a collection of configuration files that are executed before the shell becomes available for use. However, the specific configuration files that are applied depend on the type of shell you are using, whether it’s a login shell, interactive shell, or a non-interactive shell. Each type follows a different set of rules for loading configuration files.

In the following sections, we’ll dive into the available Bash configuration files, their purposes, and how they relate to different shell types. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of how these files work together to customize your Bash environment. Let’s get started!

Available configuration files

Much like many other programs, Bash uses configuration files (or “config files”) to allow users to set parameters and define initial settings. For instance, imagine you’ve written a custom function to perform a specific task. While you can define and use the function directly in your current terminal session, it will be lost once the session ends. Even if the session remains open, a new terminal window won’t have access to the function unless you redefine it.

To make the function persist across sessions and be accessible in all terminal windows, you need to include it in a configuration file. These files are automatically loaded when a terminal starts, ensuring that your customizations, like functions, aliases, and environment variables, are always ready to use.

Configuration file “/etc/profile”

The “/etc/profile” file contains system-wide environment settings and startup scripts for Linux. Its primary purpose is to configure global settings that apply to all users on the system. Typically, this script handles tasks such as:

- Configuring the default command-line prompt

- Defining the “

PATH” environment variable - Setting user limits

This script is executed only for login shells and does not run when a non-login shell or script is executed. A key part of “/etc/profile” involves checking for the existence of the “/etc/profile.d” directory, which allows for additional customization.

System administrators can modify “/etc/profile” to tailor the system’s behavior. Best practices suggest:

- Using /etc/profile for small, straightforward changes

- Creating separate scripts in the “

/etc/profile.d” directory for larger or application-specific configurations

The scripts in “/etc/profile.d” are “sourced”[1] by “/etc/profile”. This means that “/etc/profile” contains logic to identify and execute these additional scripts in a login shell. For instance, a typical snippet in “/etc/profile” might look like this:

1 # /etc/profile: system-wide .profile file for the Bourne shell (sh(1))

2 # and Bourne compatible shells (bash(1), ksh(1), ash(1), ...).

3 if [ "${PS1-}" ]; then

4 if [ "${BASH-}" ] && [ "$BASH" != "/bin/sh" ]; then

5 # The file bash.bashrc already sets the default PS1.

6 # PS1='\h:\w\$ '

7 if [ -f /etc/bash.bashrc ]; then

8 . /etc/bash.bashrc

9 fi

10 else

11 if [ "$(id -u)" -eq 0 ]; then

12 PS1='# '

13 else

14 PS1='$ '

15 fi

16 fi

17 fi

18 if [ -d /etc/profile.d ]; then

19 for i in /etc/profile.d/*.sh; do

20 if [ -r $i ]; then

21 . $i

22 fi

23 done

24 unset i

25 fi

Here’s how this code works:

- Line 18: Verifies if the “

/etc/profile.d” directory exists. - Line 19: Iterates over each script in the directory.

- Line 20: Checks if the script is readable.

- Line 21: Sources the script to execute its content.

This structure ensures modularity and makes it easier to manage system-wide configurations by allowing distinct scripts for specific tasks or applications.

Configuration File “/etc/bashrc” or Configuration File “/etc/bash.bashrc”

The “/etc/bashrc” file is a system-wide configuration file that defines functions, aliases, and other settings that apply to all users on the system. It provides a centralized way to manage configurations for Bash shells.

You may not encounter frequent references to the “/etc/bash.bashrc” file, as its origins lie in Debian[2]. This special feature was later adopted by other systems, such as Ubuntu[3]. Its use, while specific to certain distributions, serves a similar purpose: offering a global configuration for Bash environments.

In one of Debian’s README files[4], you might find a description similar to the following:

5.What is /etc/bash.bashrc? It doesn’t seem to be documented.The Debian version of bash is compiled with a special option (-DSYS_BASHRC) that makes bash read /etc/bash.bashrc before ~/.bashrc for interactive non-login shells. So, on Debian systems, /etc/bash.bashrc is to ~/.bashrc as /etc/profile is to ~/.bash_profile.

Configuration File “~/.bash_profile”

The “~/.bash_profile”, if it exists, is located in each user’s home directory. It is used to define environment variables, ensuring they are available to all future interactive shells that the user opens.

Configuration File “~/.bash_login”

Much like “~/.bash_profile”, the “~/.bash_login” file resides in the user’s home directory and is used to set environment variables, enabling future interactive shells to inherit these settings.

This file originates from the C shell’s[5] configuration file named “.login”, which inspired its creation.

Configuration File “~/.profile”

Like “~/.bash_profile” and “~/.bash_login”, the “~/.profile” file is found in the user’s home directory and is used to define environment variables, ensuring they are inherited by future interactive shells.

This file has its roots in the Bourne shell[6] and Korn shell[7], where a similar configuration file named “.profile” was first introduced.

Configuration File “~/.bashrc”

The “~/.bashrc” file is a user-specific script that Bash automatically executes whenever it starts in interactive[8] mode. It serves the same purpose as “/etc/bashrc” (or “/etc/bash.bashrc”) but is applied on a per-user basis and runs after those system-wide configuration files.

Configuration File “~/.bash_logout”

The “~/.bash_logout” file, located in the user’s home directory, is executed each time a login shell exits, provided the file exists. It serves as a counterpart to “~/.bash_login” and is designed to include commands that should run when a user logs out of the system.

For example, this file can be used to define commands for deleting temporary files or logging the duration of a user’s session.

If the file is absent, no extra commands will be executed upon logout.

Types of Shell

Bash shells can be categorized based on two key attributes:

- Whether the shell is a login shell or not.

- Whether the shell is interactive or not.

Using these attributes, we can classify shells into four distinct types:

- Interactive Login Shell

- Interactive Non-Login Shell

- Non-Interactive Non-Login Shell

- Non-Interactive Login Shell

Why is understanding this classification important? Great question! The type of shell determines which configuration files will be executed, which can significantly impact the behavior and environment of your shell session.

In the following sections, I’ll delve into each shell type, explain when and where you encounter them, and provide examples of how to create them. Let’s get started!

Interactive Login Shell

An Interactive Login Shell is initiated when you log into a system by providing your credentials.

This type of shell is commonly encountered in the following scenarios:

- Logging into a system without a graphical user interface.

- Accessing a remote server via SSH.

- Switching users with the command “

su - <username>”, which logs you in as another user. - Logging in through a virtual console (or virtual terminal) using

Ctrl+Alt+F1.

Interactive Login Shells are designed for direct user interaction, allowing you to input commands via the keyboard and view the resulting output on the screen.

Interactive Non-Login Shell

An Interactive Non-Login Shell is initiated when you are already logged into a system and open a new terminal window.

Like the Interactive Login Shell, this shell type allows direct interaction, enabling users to input commands and receive output in real time.

Non-Interactive Non-Login Shell

A Non-Interactive Non-Login Shell is created whenever you execute a script. Each script operates within its own subshell, which functions without user interaction.

While the script itself may include prompts or interactions for the user, the shell running the script remains non-interactive, handling commands silently in the background.

Non-Interactive Login Shell

A Non-Interactive Login Shell is a rare type of shell that logs into a system specifically to execute a script.

One example of this is the “ssh” command, a tool designed for logging into a remote machine to run commands without initiating a full interactive session[9].

Putting It All Together

In the previous sections, we explored the configuration files used by Bash and the different types of shells. Now, it’s time to combine this knowledge and gain a comprehensive understanding of how these configuration files relate to the various shell types.

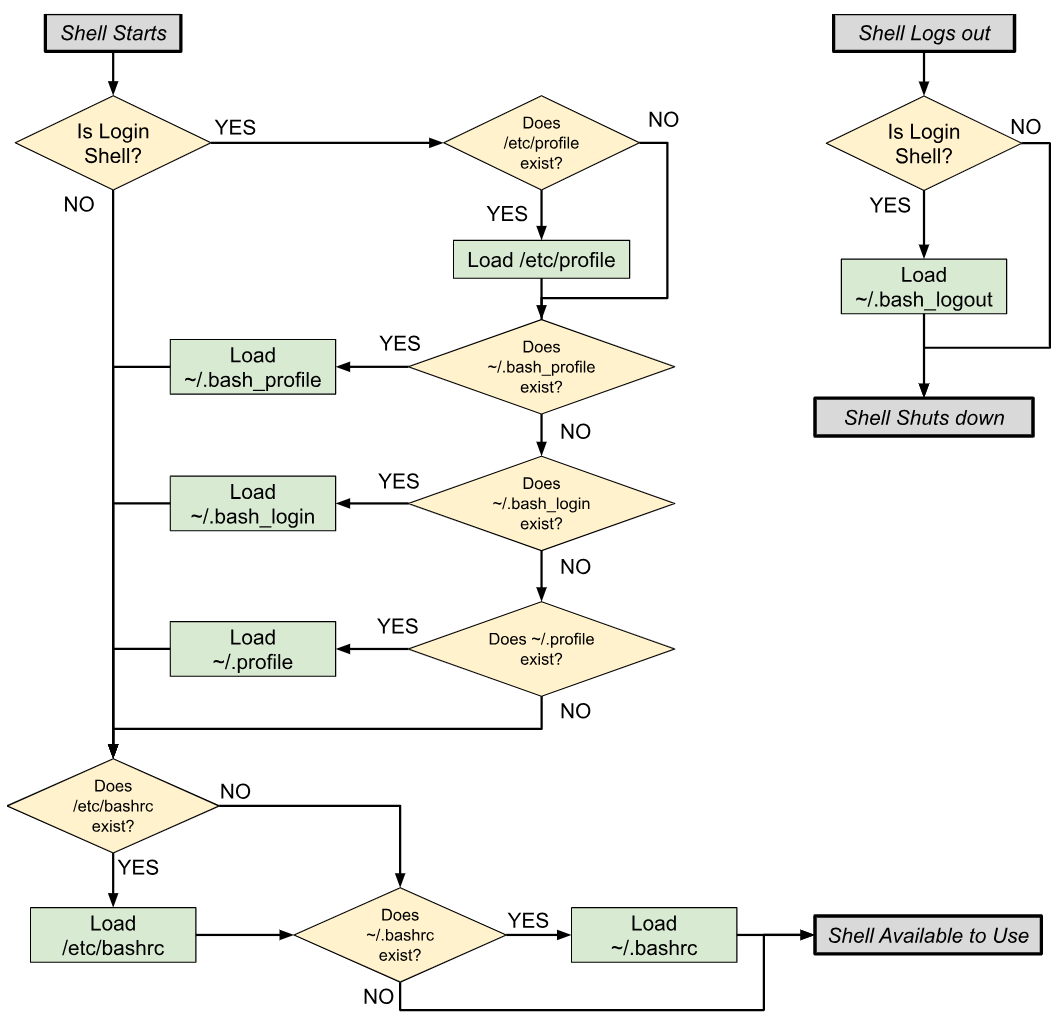

The following diagram illustrates these relationships:

This diagram applies to the following shell types:

- Interactive Login Shells

- Interactive Non-Login Shells

- Non-Interactive Login Shells

However, there is an exception for Non-Interactive Non-Login Shells, which we will address in the next section.

A Note on Non-Interactive Non-Login Shells

Non-interactive, non-login shells have a unique behavior: they do not automatically load configuration files. This design choice is intentional and stems from two key reasons.

First, it ensures independence from user-specific configurations. For instance, an alias defined by one user won’t inadvertently affect another user’s experience or scripts. Second, it prioritizes performance. A script that bypasses loading configuration files or customizations executes much faster than one that doesn’t.

If you do need to load configuration files for your script, you can explicitly source them before execution. Alternatively, you can use the “BASH_ENV” environment variable to specify a configuration file to be loaded automatically when the script runs.

For example:

$ ssh username@targethost 'BASH_ENV=/home/username/.bash_profile /home/username/my_script.sh' ...

In this case, we connect to the host targethost as the user username to execute the script “/home/username/my_script.sh”. Since the “BASH_ENV” variable is set to “/home/username/.bash_profile”, Bash will source this file before running the script.

Summary

Bash uses several configuration files to manage environment settings, commands, and customizations. These files are executed at different times, depending on the type of shell being launched. The main configuration files include “/etc/profile”, “/etc/bashrc” (or “/etc/bash.bashrc” on some systems), and user-specific files such as “~/.bash_profile”, “~/.bash_login”, “~/.profile”, “~/.bashrc”, and “~/.bash_logout”. System-wide files, such as “/etc/profile”, are run for all users, while user-specific files in the home directory apply only to the respective user. These files are essential for setting up environment variables, aliases, and other startup customizations.

Bash shells can be classified based on two attributes: whether they are interactive or non-interactive, and whether they are login or non-login. Interactive shells are those where a user can input commands directly and see the output, while non-interactive shells are typically used for running scripts. Login shells require user credentials and load configuration files meant for initializing the session, while non-login shells inherit configurations without requiring authentication.

The four types of shells are:

- Interactive Login Shell: This is launched when a user logs into the system (e.g., via SSH or a virtual console). It reads configuration files like “

/etc/profile”, “~/.bash_profile”, “~/.bash_login”, or “~/.profile”. - Interactive Non-Login Shell: This occurs when opening a new terminal window in an already logged-in session. It typically reads “

~/.bashrc” for user-specific settings. - Non-Interactive Non-Login Shell: This shell runs scripts and does not load configuration files by default to enhance performance and decouple from user-specific settings. However, configurations can be explicitly loaded by sourcing a file or setting the “

BASH_ENV” variable. - Non-Interactive Login Shell: This is rare and occurs when a login operation is performed solely to execute a script. For example, using ssh to log in and run a command remotely. It may load login shell configuration files like “

~/.bash_profile”.

Understanding the relationship between shell types and configuration files is crucial for managing Bash effectively. Each shell type has specific behavior regarding which files it reads, allowing users to tailor configurations to optimize workflows and ensure consistency across sessions.

“With the knowledge of Bash’s types of shells and configuration files, every command becomes a step toward mastery.”

References

- https://askubuntu.com/questions/438150/why-are-scripts-in-etc-profile-d-being-ignored-system-wide-bash-aliases/438170#438170

- https://askubuntu.com/questions/879364/differentiate-interactive-login-and-non-interactive-non-login-shell

- https://effective-shell.com/part-5-building-your-toolkit/configuring-the-shell/

- https://eng.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Computer_Science/Operating_Systems/Linux_-_The_Penguin_Marches_On_(McClanahan)/02%3A_User_Group_Administration/5.03%3A_System_Wide_User_Profiles/5.03.1%3A_System_Wide_User_Profiles%3A_etc-profile

- https://eng.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Computer_Science/Operating_Systems/Linux_-_The_Penguin_Marches_On_(McClanahan)/02%3A_User_Group_Administration/5.03%3A_System_Wide_User_Profiles/5.03.3System_Wide_User_Profiles%3A_The_etc-bashrc_File#.

- https://linuxhint.com/understanding_bash_shell_configuration_startup/

- https://tecadmin.net/difference-between-login-and-non-login-shell/

- https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/38175/difference-between-login-shell-and-non-login-shell

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/title/bash

- https://www.computerhope.com/unix/ubash.htm#invocation

- https://www.cyberciti.biz/faq/unix-linux-execute-command-using-ssh/

1. To “source” a script into the current script or shell you need to use the dot character (‘.’) followed by the name of the script.↩

4. https://sources.debian.org/src/bash/4.3-11/debian/README/↩

5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C_shell↩

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bourne_shell↩

7. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KornShell↩

8. More on interactive shells later in the chapter.↩

9. You can learn more about this in the next link https://www.cyberciti.biz/faq/unix-linux-execute-command-using-ssh/↩