Chapter 16: Navigation and file/folder related commands

Index

- The

pwdcommand and the variables$PWDand$OLDPWD - The

cdcommand and the$HOMEenvironment variable - The

lscommand - The

pop,popd,dirscommands and the$DIRSTACKenvironment variable - File/Folder related commands

- Summary

- References

In Bash, navigating and managing your Linux distribution involves a variety of commands that enable you to explore directories, manipulate files, and search for specific content. At the core of navigating the file system is the pwd command, which prints the current working directory, and cd, which allows you to move between directories. The ls command lists the contents of a directory, helping you view files and subdirectories at your current location. Together, these commands form the basic tools for navigating your Linux system.

Managing directories involves creating and deleting them with commands like mkdir (make a directory) and rmdir (remove an empty directory). For file creation and manipulation, touch creates new empty files, while mv moves or renames them, and rm removes files. If you want to view the contents of a file, the cat command can print it to the terminal. These commands are crucial for file and directory management, helping you control the structure and organization of your Linux environment.

Bash also provides advanced directory navigation through dirs, pushd, and popd. These commands let you manage a stack of directories, allowing you to switch back and forth between locations more efficiently. With pushd, you add a directory to the stack and move to it, while popd returns you to the previous directory. This is especially useful when working on different parts of a system without losing track of where you’ve been.

To search for files or content within files, find helps you locate files based on various criteria like name or modification time, while grep lets you search within files for specific patterns or text. These search and filtering commands are invaluable when working in larger systems or when tracking down specific information across many files. Understanding these core Bash commands equips you to efficiently navigate and manipulate your Linux environment.

In this chapter we will go a bit deeper into the commands we mentioned and will show a little bit how to use them. For a full guide of the commands please refer to the manual page[1].

Let’s begin!

The pwd command and the variables $PWD and $OLDPWD

The pwd command allows you to know what is your current working directory, and will print to the terminal window the absolute path to the directory you are in.

$ pwd

/home/username/Repositories/chapter16

The current working directory is not only avaiable via the “pwd” command, it’s also available through the environment variable “$PWD”.

There is another environment variable named “$OLDPWD” which contains the path the previous working directory you were at. When you start a session in a terminal, the initial value of this variable will be empty. At the moment of moving to another directory, the value of “$OLDPWD” will be the previous directory you were at.

Let’s see with a very simple example[2].

$ pwd

/home/username/Repositories/chapter16

$ cd script

$ echo $PWD

/home/username/Repositories/chapter16/script

$ echo $OLDPWD

/home/username/Repositories/chapter16

In the next section we will play with the “cd” command and the “$HOME” environment variable.

The cd command and the $HOME environment variable

In Bash, the “cd” (change directory) command is used to navigate between directories. It allows you to move from your current working directory to another location in the filesystem. If you use “cd” without specifying a directory, it defaults to the user’s home directory, which is represented by the environment variable “$HOME”. The “$HOME” variable stores the path to the home directory of the current user, and it is where personal files and settings are typically stored.

Here are some typical use cases so that you can use in your terminal window.

When you use “cd” without arguments will take you to your home directory, which is stored in the “$HOME” environment variable.

When you pass a single argument to the command “cd” it will get you to the directory you specified as argument. You can pass an argument that can be either an absolute path or a relative path.

What is an absolute path?

An absolute path in a Linux system is a file or directory path that starts from the root directory (/) and provides the full address to the location, regardless of the current working directory. It specifies the complete path to a file or directory from the top of the file system hierarchy. Absolute paths always start with a forward slash (/), which signifies the root directory (For example: /home/username/Documents/file.txt).

What is a relative path?

A relative path in a Linux system is a file or directory path that is relative to the current working directory, rather than starting from the root (/). Unlike absolute paths, relative paths do not begin with a /. Instead, they reference locations in relation to the directory you are currently in, making it a shorter and more flexible way to navigate the file system.

For example, if you’re currently in /home/username/Documents and you want to access file.txt in the Projects subdirectory, the relative path would be ./Projects/file.txt. Here, ./ refers to the current directory. Similarly, ../ is used to move up one directory level. So, if you want to reference a file located in /home/username, the relative path would be ../file.txt.

Another use case of the “cd” command is when you provide as argument two points like “cd ..”. This is telling Bash to move up one level in the directory hierarchy.

The last use case I can come up with is providing a dash to the “cd” command like “cd -”, using this will return you to the previous directory you were on.

Now that we played a bit with the “cd” command we are going to play with another command that will be one of the commands we will use the most, which is the “ls” command.

The ls command

The “ls” command is used to list the contents of the current directory or to list the arguments passed to it. This command is very rich in terms of flags. For a full explanation, I do recommend consulting “man ls” in your terminal.

Here, we will focus on the flags I do consider more interesting. The following table contains a few flags and description for each one of them.

| Flag | Description |

|---|---|

-1 |

(The numeric digit one) Force output to be one entry per line. This is the default when output is not to a terminal. |

-A |

List all entries except for . and ... |

-a |

List all directories including those directories whose names begin with a dot (.). |

-C |

Force multi-column output; this is the default when output is to a terminal. |

-c |

Use time when file status was last changed for sorting (-t) or long printing (-l). |

-d |

Directories are listed as plain files (not searched recursively) |

-G |

Enable colorized output |

-h |

When used with the -l option, use unit suffixes: Byte, Kilobyte, Megabyte, Gigabyte, Terabyte and Petabyte in order to reduce the number of digits to three or less using base 2 for sizes |

-l |

(The lowercase letter “ell”.) List in long format. If the output is to a terminal, a total sum for all the file sizes is output on a line before the long listing |

-m |

Stream output format; list files across the page, separated by commas |

-R |

Recursively list subdirectories encountered. |

-r |

Reverse the order of the sort to get reverse lexicographical order or the oldest entries first or largest files last, if combined with sort by size |

-S |

Sort files by size |

-T |

When used with the -l (lowercase letter “ell”) option, display complete time information for the file, including month, day, hour, minute, second, and year. |

-t |

Sort by time modified (most recently modified first) before sorting the operands by lexicographical order |

-u |

Use time of last access, instead of last modification of the file for sorting (-t) or long printing (-l) |

-U |

Use time of file creation, instead of last modification for sorting (-t) or long output (-l) |

When you use the “ls” command in Bash with the “-l” flag, it provides a detailed listing of files and directories in the current directory. Here’s a breakdown of the information printed on the terminal window.

- File Type and Permissions: The first column indicates the file type and its permissions. It consists of 10 characters.

- The first character indicates the file type (

-for a regular file,dfor a directory,lfor a symbolic link, etc.) - The next nine characters show the file’s permissions in three groups: owner, group, and others. For example,

rwxr-xr--means:- Owner has read, write, and execute permissions (

rwx) - Group has read and execute permissions (

r-x) - Others have read-only permissions (

r--)

- Owner has read, write, and execute permissions (

- The first character indicates the file type (

- Number of Links: The second column shows the number of hard links to the file or directory. For directories, this count includes the directory itself and its subdirectories.

- Owner: The third column displays the name of the user (owner) who owns the file.

- Group: The fourth column shows the name of the group that has permissions for the file.

- File Size: The fifth column indicates the size of the file in bytes. For large files, you may want to use the

-hflag with-lto display file sizes in a human-readable format (e.g., KB, MB). - Modification Date and Time: The sixth column gives the date and time when the file was last modified. The format is typically

MMM DD HH:MMfor files modified in the current year, andMMM DD YYYYfor older files. - File Name: The final column shows the name of the file or directory. If it is a symbolic link, it will also display the link target.

Let’s take a look at the following example.

$ ls -l

-rwxr-xr-- 1 user group 4096 Oct 3 12:00 myfile.txt

drwxr-xr-x 2 user group 4096 Oct 3 11:55 mydirectory

In the previous example:

- The first entry (

myfile.txt) is a regular file withrwxr-xr--permissions, owned byuserin thegroupgroup, and is 4096 bytes in size. - The second entry (

mydirectory) is a directory, withrwxr-xr-xpermissions, and contains two links (itself and a subdirectory).

This detailed view is useful for checking file permissions, ownership, and modification dates at a glance.

In the next section we will play with “pushd”, “popd”, “dirs” and “$DIRSTACK”.

The pop, popd, dirs commands and the $DIRSTACK environment variable

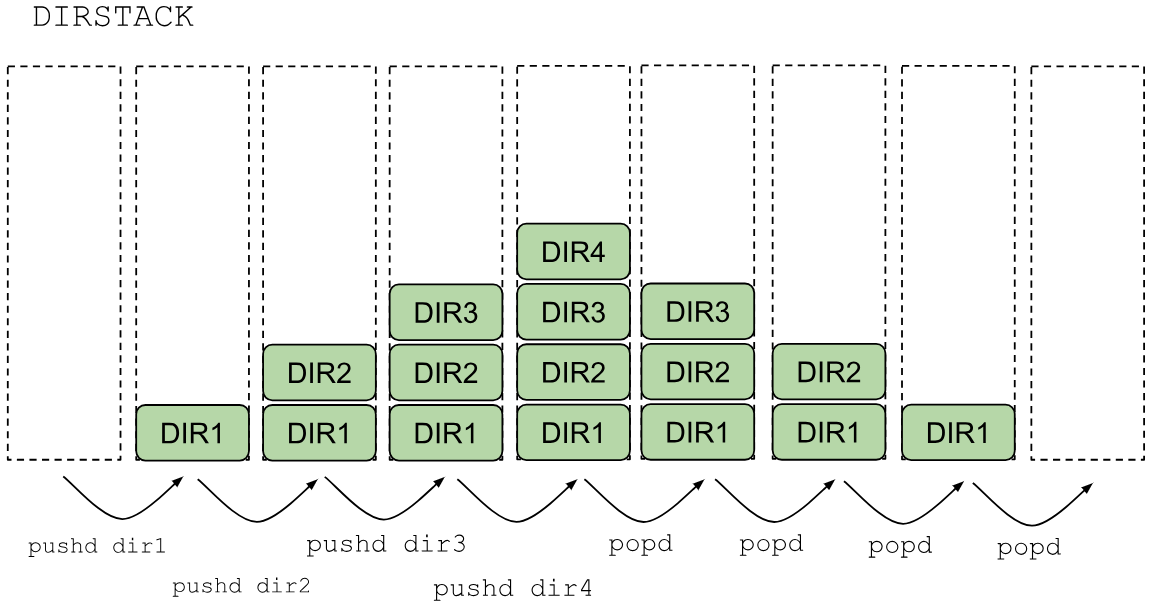

The “pushd”, “popd”, and “dirs” are shell builtins which allow you manipulate the directory stack ($DIRSTACK). This can be used to change directories but return to the directory from which you came.

How can we visualize the stack of directories?

The pushd command

This builtin command is in charge of adding directories to DIRSTACK. Typically, “pushd” is invoked with a parameter which is the path to a directory which will be set a new current working directory and the one that will be put on top of the stack.

If invoked with no arguments, it will exchange the first two items on top of the stack, and it will change as well the current working directory. Let’s say that your current working directory is your home directory and that you have inside DIRSTACK two directories, which are your home directory (typically represented with ~) and the /tmp directory.

If you invoke “pushd” without arguments, your current working directory will become “/tmp”. This means that the “/tmp” will be put on top of the DIRSTACK and your home folder (~) will be the second in the stack.

If there are not enough items on the stack, it will throw an error.

This command comes as well with other options that modify (or not) the stack in specific ways.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-n |

Manipulates the stack but without changing the current working directory |

+N |

Rotates the stack so that the Nth directory (counting from the left of the list shown by dirs, starting with zero) is at the top. |

-N |

Rotates the stack so that the Nth directory (counting from the right of the list shown by dirs, starting with zero) is at the top. |

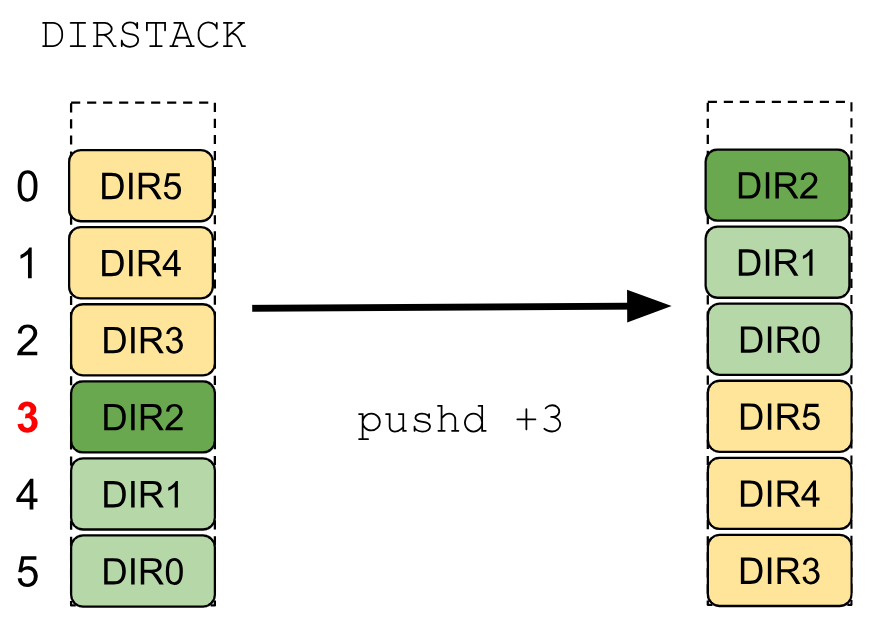

Let’s see a graphical representation of “pushd +N”.

So… What is going on in the previous image? The DIRSTACK environment variable has 6 directories pushed to it being DIR0 the first one to be pushed and being DIR5 the last one to be pushed to the stack DIRSTACK (and also is the current working directory).

When the command “pushd +3” is executed, the folder on the index 3 (“DIR2” in our case) will be moved to the top of the stack along with the directories that are in the following indices. Another effect of this command is that all the directories from the top of the stack until the index before the index that was passed to the command “pushd” will be sent to the bottom of the stack in the same order that they were on the top.

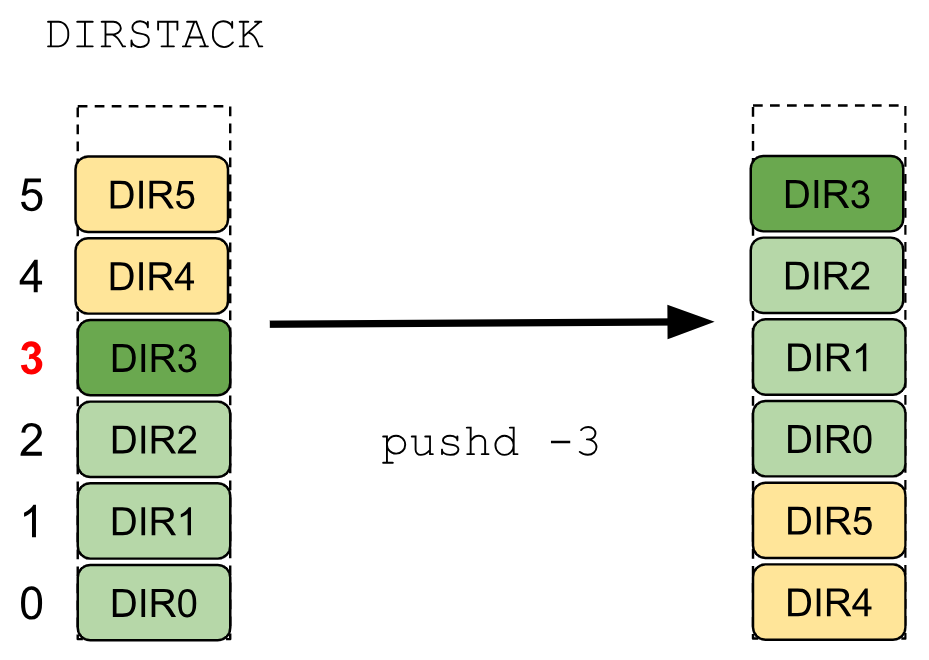

In the following image you will see a graphical representation of “pushd -N”.

So… What is going on in the previous image? The DIRSTACK environment variable has the same configuration as in the previous example.

When the command “pushd -3” is executed, the folder on the index 3 (“DIR3” in our case) will be moved to the top of the stack along with the directories that are in the previous indices (“DIR2”, “DIR1” and “DIR0” in our case). Another effect of this command is that all the directories from the top of the stack until the index after the index that was passed to the command “pushd” will be sent to the bottom of the stack in the same order that they were on the top.

The popd command

This builtin command is in charge of removing directories to DIRSTACK. Typically, “popd” is invoked without parameters which result in the removal of the item located at the top of the stack. This will result (similar to the “pushd” command) in updating the current working directory to the next element in the stack.

This command comes as well with other options that modify (or not) the stack in specific ways.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-n |

Manipulates the stack but without changing the current working directory. |

+N |

Removes the Nth entry counting from the left of the list shown by dirs, starting with zero. For example: popd +0 removes the first directory, popd +1 the second. |

-N |

Removes the Nth entry counting from the right of the list shown by dirs, starting with zero. For example: popd -0 removes the last directory, popd -1 the next to last. |

The dirs command

This builtin command of Bash is in charge of displaying the contents of the DIRSTACK environment variables. This command comes with the following options.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-c |

Clears the directory stack by deleting all of the elements. |

-l |

Do not print tilde-prefixed versions of directories relative to your home directory. Will print all the directories in the “$DIRTACK” environment variable with absolute paths. |

-p |

Print the directory stack with one entry per line. |

-v |

Print the directory stack with one entry per line prefixed with its position in the stack. |

+N |

Displays the Nth entry counting from the left of the list shown by dirs when invoked without options, starting with zero. |

-N |

Displays the Nth entry counting from the right of the list shown by dirs when invoked without options, starting with zero. |

In the following sections, we will learn a little bit of how to create files and folders, how to show the content of files, how to move folders or files around, how to delete files and folders and, most importantly how to to search information in different files/folders.

File/Folder related commands

In the earlier sections, we explored how to navigate the filesystem and view the contents of directories. Now, in the upcoming subsections, we will focus on essential file and folder operations, including how to:

- Create new files and directories

- View the contents of a file

- Move or rename files and directories

- Delete files and directories

- Search for files or directories based on specific criteria

These tasks form the foundation of file management in Bash and are key to efficiently working within the command-line environment.

Creation of files

There are several ways to create files, but for now, we’ll focus on a straightforward command that allows us to quickly generate an empty file: the “touch” command.

Primarily, “touch” is designed to update the access and modification timestamps of an existing file. However, if you provide the name (or path) of a file that doesn’t already exist, “touch” will create that file for you automatically.

One key feature of “touch” is its ability to handle multiple filenames at once, enabling you to create several files simultaneously by simply listing their names.

The “touch” command makes very easy creating new files. You can also use text editors like VIM[3], Notepad or similar ones to create text files.

Let’s give it a try with this command.

$ ls

$ touch file.txt

$ ls

file.txt

In the previous example we went to a directory that had no files nor folders in it. Then we used thecommand “ls” to list everything in the directory (which is nothing). Then we used the command “touch file.txt” to create a file with the name of “file.txt”. Then we used (again) the command “ls” to list (again) the contents of the current folder. This time it shows the new file that we created.

Creation of directories

We’ve learned how to view the contents of a folder, but how do we create one? For that, we use the command “mkdir”, short for “make directory.”

One of the great features of “mkdir” is its ability to accept multiple arguments, allowing you to create several directories at once. However, there’s a potential complication—sometimes you might need to create a directory within another directory, or even at a deeper level. In such cases, the parent directories of your target folder must already exist.

To address this limitation, “mkdir” provides a handy “-p” option. This option ensures that all necessary intermediate directories are created automatically, allowing you to build an entire directory structure in one go.

Let’s see a few examples in the terminal window.

$ ls

file.txt

$ mkdir directory1/directory2

mkdir: cannot create directory ‘directory1/directory2’: No such file or directory

$ mkdir -p directory1/directory2

$ ls

directory1 file.txt

As you can see in the previous example, we first used the command “ls” to list the contents of the current folder, which contains the file “file.txt” that we created previously.

Then we tried to create 2 folders being “directory1” the first one and being “directory2” the second one, inside the first directory with the command “mkdir” (without any additional options). As you can see it failed.

But if we add the option “-p” it works.

Last we use the command “ls” to show the new content of the current directory.

In the next section we will learn how to use the command “cat”.

Show content of a file (The cat command)

We’ve learned how to create files and directories, but how do we view the contents of those files in Bash? This is where the command cat comes in handy. Its primary function is to read the contents of one or more files and print them to the standard output, which is usually your terminal screen. The basic syntax of cat is as follows:

cat [-benstuv] [file ...]

With “cat”, you can display the contents of a single file or multiple files in the order they are provided. If you pass “-” as an argument, “cat” will wait for input from the standard input (such as typing into the terminal), and it will display whatever you type. Invoking “cat” with no arguments is equivalent to using “cat -”, meaning it will echo back whatever you type.

There are a few useful flags with “cat”:

- ”

-b”: Numbers only non-blank lines in the output, starting from 1. - ”

-n”: Numbers all lines, blank or non-blank, starting from 1. - ”

-s”: Reduces multiple consecutive blank lines in the output to a single blank line, making the output more readable if the file contains a lot of empty space.

In summary, “cat” is a straightforward and versatile tool for quickly viewing file contents, but with a few useful flags, it can also tidy up your output for better readability.

Let’s say we want to display the content of the file we created before (the file “file.txt”). For that we can use the “cat” command as follows.

$ cat file.txt

Content of line 1

Content of line 2

Content of line 3

Content of line 4

Content of line 5

Now that have learnt how to show the contents of a file using the “cat” command we are going to take a look to the “mv” command which will allow us to move files and directories.

Moving files and folders (The mv command)

The “mv” command in Bash is a versatile tool used for moving files and directories from one location to another or simply renaming them. Its basic functionality makes it essential for organizing files and directories within your Linux system. The “mv” command can be invoked in two common forms, depending on the task at hand.

In the first form, “mv source target”, the command is used to rename a file or folder. You specify the source (the existing file or directory) and the target (the new name or location). If the target is a new name, the source will be renamed.

For example to rename a file named “report.txt” to “summary.txt” you can use the “mv” command as follows.

$ mv report.txt summary.txt

You can also use the “mv” command to rename directories like the following.

$ mv directory1 directory2

The previous example will rename a directory named “directory1” to “directory2”.

In the second form, “mv source... directory”, the command moves one or more files or directories to a specified directory. Here, all the source files are relocated into the specified directory. When using this form, the last argument must always be an existing directory.

Let’s say you want to move a text file inside of a folder. You could do it as follows.

$ mv summary.txt Documents/

In the previous example you are moving the file “summary.txt” to the folder “Documents”

You can also use the “mv” command to move several items (either files or folders) to a single folder. You can do it in the following way.

$ mv file1.txt directory1 file2.txt Documents/

In the previous example the files “file1.txt”, “file2.txt” and the folder “directory1” were moved inside the directory “Documents”.

In the next section we are going to learn how to delete directories.

Deletion of files and folders (The commands rm and rmdir)

To delete files and directories in Bash, you have two powerful commands at your disposal: “rm” and “rmdir”. While they both serve similar purposes, there are important differences in how they function.

The “rmdir” command is used specifically for removing empty directories. It ensures that the directory being deleted contains no files or subdirectories. If you want to delete a nested directory structure, you can use the “-p” option, which allows “rmdir” to remove the entire path of empty directories. For example, if you have a structure like “test1/test2/test3”, using “rmdir -p test1/test2/test3” will remove all the directories in the path, provided they are all empty.

On the other hand, the “rm” command is more versatile. It is mainly used to delete individual files but can also remove entire directories if used with the “-r” (recursive) option. This means that it will delete a directory along with all its contents, making it a much more powerful and potentially dangerous command. If you use “rm” with the “-f” (force) option, the command will suppress any warnings or prompts, immediately deleting files and directories without confirmation. However, this should be used with caution to avoid accidental deletion of important files. For extra security, you can use the “-i” (interactive) option, which will prompt you to confirm each file or directory deletion.

In summary, use “rmdir” for cleanly removing empty directories and “rm” for more aggressive file and folder deletions. Be careful with options like “-r” and “-f” to avoid unintentional deletions!

In the next section we are going to learn how to use the commands “grep” and “find” which will be the key to find anything in your file directory system.

Searching (The commands grep and find)

As you continue working with files and directories in Bash, mastering the ability to search for specific data is crucial. Whether you’re trying to locate a particular file, examine its contents, or search through hundreds of files for a specific pattern, efficient searching techniques will save you time and effort. Two of the most essential commands to help you with this are “grep” and “find”. These commands are incredibly versatile and powerful when it comes to searching for data based on different criteria.

The “grep” command is used to search within files for a particular string or pattern. It allows you to quickly locate lines in a file that match a specific search pattern, making it invaluable for examining log files, looking for specific keywords in scripts, or filtering out necessary information from large files. You can even combine “grep” with other commands in pipelines to process and filter data more efficiently. This tool becomes indispensable when working with large amounts of text or multiple files, as it allows you to extract meaningful information without having to open each file manually.

On the other hand, “find” is a command that helps you locate files and directories on your system based on a variety of criteria, such as name, size, modification date, or file type. If you’ve ever lost track of where you saved a file or need to find all files matching certain characteristics in a directory tree, “find” is your go-to tool. It can perform searches recursively and allows you to specify detailed filters to refine your search, making it extremely flexible for file management. Moreover, “find” can be combined with other commands to perform actions on the files it locates, like moving or deleting them.

Learning to use “grep” and “find” effectively is vital for improving your productivity in a Linux environment. These commands give you the power to quickly sift through vast amounts of data, locate key files, and even perform operations on them—all from the command line. As your experience with Bash grows, these tools will become an integral part of your toolkit, enabling you to work faster and more efficiently.

The find command

The find command in Unix-based systems is an incredibly powerful tool for locating files and directories based on various criteria you define. Its versatility and range of options make it indispensable for managing files across complex directory structures. Here’s an overview of how to use it effectively.

The basic syntax of the find command is:

find [options] [paths] [expressions]

Where:

- Options: These specify how the search should be conducted. For example, should it follow symbolic links, or should directories be searched in a specific order? Some key options include:

- ”

-L”: This tells find to follow symbolic links, meaning it will show information about the file or directory the link points to, rather than the link itself. - ”

-d”: This option ensures a depth-first search, meaning directories are processed after their contents. Without this option, the default search is pre-order, meaning directories are processed before their contents. - ”

-s”: Causes find to search hierarchies in lexicographical (alphabetical) order within each directory. - ”

-f”: Specifies a particular directory hierarchy to search. For instance, this option allows you to designate multiple directories for find to search through.

- ”

- Paths: This part of the command specifies the starting point(s) for the search. You can provide one or multiple directories. If no path is provided, it defaults to the current working directory.

- Expressions: These are the heart of the command. They allow you to specify search criteria (predicates) and define actions that should be taken on the matching files. The expressions can include:

- Predicates: Conditions that evaluate to true or false for each file or directory. Only items matching all the given predicates will be included in the result. Examples include:

- ”

-name filename”: Finds files with a specific name. - ”

-type d”: Limits the search to directories. - ”

-size +100M”: Finds files larger than 100 MB.

- ”

- Actions: Once a file or directory matches the given predicates, you can define actions to perform. Examples include:

- ”

-exec command {} \;”: Runs a specified command on the matched files or directories. - ”

-delete”: Deletes the matching files or directories.

- ”

- Predicates: Conditions that evaluate to true or false for each file or directory. Only items matching all the given predicates will be included in the result. Examples include:

Logical operators can be used to combine expressions for more complex queries:

- ”

( expression )”: Groups expressions to control the order of evaluation. - ”

! expression” or “-not expression”: Negates the result of the expression. - “

expression -and expression”: Combines two expressions, both must be true. - “

expression -or expression”: Either of the expressions must be true.

The following table contains what are the different predicates you can use and the description for each one of them.

| Predicate | Description |

|---|---|

-empty |

True if the current file or directory is empty. |

-group gname |

True if the file belongs to the group gname. If gname is numeric and there is no such group name, then gname is treated as a group ID. |

-name pattern |

True if the last component of the pathname being examined matches the pattern provided. Special shell pattern matching characters ([, ], *, and ?) may be used as part of pattern. These characters may be matched explicitly by escaping them with a backslash (\). It’s recommended to put “pattern” between single quotes ('...') or double quotes ("..."). |

-iname pattern |

Like -name, but the match is case insensitive. |

-nouser |

True if the file belongs to an unknown user. |

-size n[ckMGTP] |

True if the file’s size, rounded up, in 512-byte blocks is n. If n is followed by a c, then the primary is true if the file’s size is n bytes (characters). Similarly if n is followed by a scale indicator then the file’s size is compared to n scaled as follows. k kilobytes (1024 bytes), M megabytes (1024 kilobytes), G gigabytes (1024 megabytes), T terabytes (1024 gigabytes) and P petabytes (1024 terabytes). |

-type t |

True if the file is of the specified type. Possible file types are as follows. b (block special), c (character special), d (directory), f (regular file), l (symbolic link), p (FIFO, pipe), s (socket) |

-user uname |

True if the file belongs to the user uname. If uname is numeric and there is no such user name, then uname is treated as a user ID. |

Let’s say that we have the following files and directories in our current working directory.

.

├── directory-1

│ ├── directory-1

│ │ └── file-directory1-1.txt

│ ├── directory-2

│ ├── directory-3

│ │ └── file-directory1-1.txt

│ ├── directory-4

│ └── directory-5

│ └── file-directory1-1.txt

├── directory-2

│ ├── directory-1

│ ├── directory-2

│ ├── directory-3

│ ├── directory-4

│ └── directory-5

├── directory-3

│ ├── directory-1

│ ├── directory-2

│ ├── directory-3

│ │ └── file-directory3-3.txt

│ ├── directory-4

│ │ └── file-directory3-4.txt

│ └── directory-5

├── directory-4

│ ├── directory-1

│ ├── directory-2

│ │ └── file-directory4-2.txt

│ ├── directory-3

│ ├── directory-4

│ │ └── file-directory4-4.txt

│ └── directory-5

│ └── file-directory4-5.txt

├── directory-5

│ ├── directory-1

│ ├── directory-2

│ │ └── file-directory5-2.txt

│ ├── directory-3

│ ├── directory-4

│ │ └── file-directory5-4.txt

│ └── directory-5

│ └── file-directory5-5.txt

├── directory-6

│ ├── directory-1

│ │ └── file-directory6-1.png

│ ├── directory-2

│ ├── directory-3

│ │ └── file-directory6-3.png

│ ├── directory-4

│ │ └── file-directory6-4.mp4

│ └── directory-5

├── directory-7

│ ├── directory-1

│ │ └── file-directory7-1.txt

│ ├── directory-2

│ │ └── file-directory7-2.gif

│ ├── directory-3

│ ├── directory-4

│ └── directory-5

├── file-1.txt

├── file-2.txt

├── file-3.txt

├── file-4.txt

├── file-5.txt

├── file-6.txt

└── file-7.txt

You can see that we have TXT files, PNG files, GIF files and MP4 files.

Let’s say that we want to find the files that are empty. for that we could use the predicate “-empty” and the predicate “-type f” like the following.

$ find . -empty -type f

./directory-3/directory-3/file-directory3-3.txt

./directory-3/directory-4/file-directory3-4.txt

./file-1.txt

./directory-7/directory-2/file-directory7-2.gif

./directory-7/directory-1/file-directory7-1.txt

./directory-5/directory-5/file-directory5-5.txt

./directory-5/directory-4/file-directory5-4.txt

./directory-5/directory-2/file-directory5-2.txt

./directory-6/directory-3/file-directory6-3.png

./directory-6/directory-4/file-directory6-4.mp4

./directory-6/directory-1/file-directory6-1.png

./file-4.txt

./directory-4/directory-5/file-directory4-5.txt

./directory-4/directory-4/file-directory4-4.txt

./directory-4/directory-2/file-directory4-2.txt

./file-5.txt

./file-2.txt

./file-3.txt

./file-6.txt

./directory-1/directory-3/file-directory1-1.txt

./directory-1/directory-5/file-directory1-1.txt

./directory-1/directory-1/file-directory1-1.txt

./file-7.txt

With the predicate “-empty” we are requesting the “find” command to provide the files or directories that are empty, with the predicate “-type f” we are requesting the “find” command to provide only regular files.

Let’s say that we want to get the files of the user with name “username” for that we can use the “find” command as follows.

$ find . -user username

.

./directory-3

./directory-3/directory-3

./directory-3/directory-3/file-directory3-3.txt

./directory-3/directory-5

./directory-3/directory-4

./directory-3/directory-4/file-directory3-4.txt

./directory-3/directory-2

./directory-3/directory-1

./file-1.txt

./directory-7

./directory-7/directory-3

./directory-7/directory-5

./directory-7/directory-4

./directory-7/directory-2

./directory-7/directory-2/file-directory7-2.gif

./directory-7/directory-1

./directory-7/directory-1/file-directory7-1.txt

./directory-5

./directory-5/directory-3

./directory-5/directory-5

./directory-5/directory-5/file-directory5-5.txt

./directory-5/directory-4

./directory-5/directory-4/file-directory5-4.txt

./directory-5/directory-2

./directory-5/directory-2/file-directory5-2.txt

./directory-5/directory-1

./directory-6

./directory-6/directory-3

./directory-6/directory-3/file-directory6-3.png

./directory-6/directory-5

./directory-6/directory-4

./directory-6/directory-4/file-directory6-4.mp4

./directory-6/directory-2

./directory-6/directory-1

./directory-6/directory-1/file-directory6-1.png

./file-4.txt

./directory-4

./directory-4/directory-3

./directory-4/directory-5

./directory-4/directory-5/file-directory4-5.txt

./directory-4/directory-4

./directory-4/directory-4/file-directory4-4.txt

./directory-4/directory-2

./directory-4/directory-2/file-directory4-2.txt

./directory-4/directory-1

./file-5.txt

./file-2.txt

./file-3.txt

./directory-2

./directory-2/directory-3

./directory-2/directory-5

./directory-2/directory-4

./directory-2/directory-2

./directory-2/directory-1

./file-6.txt

./directory-1

./directory-1/directory-3

./directory-1/directory-3/file-directory1-1.txt

./directory-1/directory-5

./directory-1/directory-5/file-directory1-1.txt

./directory-1/directory-4

./directory-1/directory-2

./directory-1/directory-1

./directory-1/directory-1/file-directory1-1.txt

./file-7.txt

As you can see the “find” command returns all files and directories as all of them were created by the user with name “username”.

But the “find” command allows you as well to execute actions on the files or directories that match the predicate provided.

The following table contains the most popular actions that I have used.

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

-delete |

Delete found files and/or directories. Always returns true. This executes from the current working directory as find recurses down the tree. It will not attempt to delete a filename with a / character in its pathname relative to . for security reasons. Depth-first traversal processing is implied by this option. Following symlinks is incompatible with this option. |

-exec utility [argument ...] \; |

True if the program named utility returns a zero value as its exit status. Optional arguments may be passed to the utility. The expression must be terminated by a semicolon (;). If you invoke find from a shell you may need to quote the semicolon if the shell would otherwise treat it as a control operator. If the string {} appears anywhere in the utility name or the arguments it is replaced by the pathname of the current file. Utility will be executed from the directory from which find was executed. Utility and arguments are not subject to the further expansion of shell patterns and constructs. |

-exec utility [argument ...] \+ |

Same as the previous one, except that {} is replaced with as many path names as possible for each invocation of utility. |

-ls |

This primary always evaluates to true. The following information for the current file is written to standard output: inode number, size in 512-byte blocks, file permissions, number of hard links, owner, group, size in bytes, last modification time, path name. If the file is a block or character special file, the device number will be displayed instead of the size in bytes. If the file is a symbolic link, the pathname of the linked-to file will be displayed preceded by ->. The format is identical to that produced by “ls -dgils”. |

For a deeper explanation and understanding of the actions and predicates that you can use with the “find” command please consult the manual page[4].

In the next section we will learn how to use the “grep” command.

The grep command

The “grep” command is one of the most powerful and widely-used tools for searching through text in files. It’s a versatile command that allows users to look for specific patterns within files, making it essential for tasks like filtering logs, extracting data, and debugging scripts. By understanding the basic syntax and options available, you can leverage “grep” to perform a variety of searches efficiently.

At its core, “grep” searches for a given pattern of text within one or more files. The basic syntax is as follows:

grep [options] [pattern] [file...]

Where:

- Pattern: This is the string or regular expression you’re searching for in the file(s).

- File: This is the location of the file(s) where the search will be conducted. If no file is provided, “

grep” searches through standard input (i.e., what you type in the terminal or output from another command).

The following table contains the options that I have used the most.

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-A num |

Print num lines of trailing context after each match. |

-B num |

Print num lines of leading context before each match. |

-C [num] |

Print num lines of leading and trailing context surrounding each match. The default is 2 and is equivalent to -A 2 -B 2. |

-c |

Only a count of selected lines is written to standard output. |

--color |

Color the result. |

-e pattern |

Specify a pattern used during the search of the input: an input line is selected if it matches any of the specified patterns. This option is most useful when multiple -e options are used to specify multiple patterns, or when a pattern begins with a dash (-). |

-f file/--file=file |

Obtain patterns from file, one per line. The empty file contains zero patterns, and therefore matches nothing. |

-i |

Perform case insensitive matching. By default, grep is case sensitive. |

-n |

Each output line is preceded by its relative line number in the file, starting at line 1. The line number counter is reset for each file processed. |

-r/--recursive |

Read all files under each directory, recursively, following symbolic links only if they are on the command line. Note that if no file operand is given, grep searches the working directory. |

-R/--dereference-recursive |

Read all files under each directory, recursively. Follow all symbolic links, unlike -r. |

-v/--invert-match |

Selected lines are those not matching any of the specified patterns. |

Let’s say that we want to find the files that contain the word “Lorem” and the line where this word appears in the previous working directory. For that we use the “grep” command as follows.

$ grep -r -n -e "Lorem" .

./directory-3/directory-3/file-directory3-3.txt:1:Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

./file-7.txt:1:Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

For deeper details on the “grep” command please check its manual page[5].

In the next section we will learn to combine the commands “find” and “grep”.

Combining the commands find and grep

When it comes to combining the power of the “find” and “grep” commands, you’re leveraging two highly efficient tools to search for files and patterns inside those files. “find” excels at locating files based on various attributes (like file name, size, or modification time), while “grep” is perfect for identifying specific patterns within those files. By combining these two, you can narrow down your search to both file names and content, creating a highly targeted and efficient workflow.

The “find” command has a powerful option, “-exec”, which allows you to run another command on each file found that matches your criteria. This is where the magic happens: you can use “find” to locate files and then automatically pass those files to “grep” to search for specific patterns inside them.

Here’s an example of how this combination works:

find . -type f -name "function*.sh" -exec grep -n --color custom {} \;

This command does the following:

- “

find .”: Searches from the current directory (.). - ”

-type f”: Restricts the search to regular files (not directories). - ”

-name "function*.sh"”: Looks for files that start with “function” and end with “.sh”. - ”

-exec grep -n --color custom {}”: Executes grep on each of the found files. The “{}” placeholder is where each file’s path will be inserted. - ”

\;”: Tells find to execute grep once per file.

In this case, grep will search each file for the word “custom”, display the matching line number (-n), and highlight the match with color (--color).

If you want to make the process more efficient, especially when searching through a large number of files, you can use the “+” at the end of the “-exec” option to pass all the matching files to “grep” at once rather than executing grep separately for each file:

find . -type f -name "function*.sh" -exec grep -n --color custom {} \+

This way, “grep” runs a single time and processes all the found files together, improving performance when you are dealing with many files.

By mastering the combination of “find” and “grep”, you’ll have a highly efficient method of pinpointing files and extracting useful information from them, saving you time when working in complex file structures.

Summary

In this chapter, we explored several essential commands and environment variables that help us navigate and manipulate the file system from the command line. We began by understanding how to track our current directory using “pwd”, with the “$PWD” environment variable holding the present working directory and “$OLDPWD” keeping track of the previous one. The command “cd” allows you to move between directories, and “$HOME” serves as the shortcut to return to your home directory no matter where you are. To list files within a directory, we use the “ls” command, which comes with a variety of options for displaying detailed file information.

We also covered how to manage directories with “mkdir” for creating new directories and “rmdir” for removing empty ones. For more complex file management tasks, the “rm” command can delete both files and directories, while “mv” is used to move or rename files. We touched on stack navigation using “dirs”, “pushd”, and “popd”, which allow you to push and pop directories onto a stack for easier navigation between multiple paths.

When it comes to inspecting file contents, “cat” enables you to quickly view the contents of a file, making it useful for examining configurations or logs. Searching for specific information within files can be efficiently done with the “grep” command, which matches patterns in files. Finally, the powerful “find” command allows you to locate files and directories based on criteria such as name, size, and timestamps, and even execute additional commands on the results, like piping them to “grep” for pattern searching.

Remember, mastering these commands comes with practice. Every time you work in the command line, challenge yourself to use these tools more effectively. As the saying goes, “Repetition is the mother of skill.” So keep exploring, keep experimenting, and soon enough, these commands will become second nature.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ls

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pushd_and_popd

- https://linuxize.com/post/how-to-find-files-in-linux-using-the-command-line/

- https://linuxize.com/post/linux-cd-command/

- https://opensource.com/article/19/8/navigating-bash-shell-pushd-popd

- https://phoenixnap.com/kb/create-directory-linux-mkdir-command

- https://phoenixnap.com/kb/linux-cat-command

- https://www.baeldung.com/linux/find-exec-command

- https://www.cyberciti.biz/faq/howto-use-grep-command-in-linux-unix/

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/grep-command-in-linux-unix

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/cat-command-in-linux-with-examples/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/cd-command-in-linux-with-examples/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/find-command-in-linux-with-examples/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/grep-command-in-unixlinux/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/mkdir-command-in-linux-with-examples/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/rm-command-linux-examples/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/rmdir-command-in-linux-with-examples/

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/touch-command-in-linux-with-examples/

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/bg/aix/7.2?topic=t-touch-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/aix/7.1?topic=directories-creating-mkdir-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/aix/7.1?topic=directories-deleting-removing-rmdir-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/aix/7.1?topic=files-deleting-rm-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/aix/7.1?topic=files-moving-renaming-mv-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/es/aix/7.1?topic=m-mv-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/kk/aix/7.1?topic=c-cat-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/ru/aix/7.2?topic=c-cd-command

- https://www.ibm.com/docs/tr/aix/7.1?topic=p-pwd-command

- https://www.maths.cam.ac.uk/computing/linux/unixinfo/ls

- https://www.redhat.com/sysadmin/linux-find-command

- https://www.serveracademy.com/blog/how-to-use-the-touch-command-in-linux/

1. Please refer to man ls, man cd,...↩

2. We will learn more about the "cd" later in this chapter.↩

3. More about this powerful editor in its website https://www.vim.org/.↩

4. Just type "man find" in your terminal window.↩

5. Just type "man grep" in your terminal window.↩